To Meet New York’s Childcare Crisis, Cut Red Tape and Increase Wages

The State budget proposed by Governor Kathy Hochul earlier this month includes $1.7 billion to support child care statewide. That’s about the same as last year's commitment. The governor's proposal also would make it easier for more families to access affordable child care.

Nevertheless, the budget misses the central element in New York State's grievous inability to deliver childcare:

Raising wages to a level that will attract, and keep, qualified and dedicated childcare workers, and fill the gaping shortages in this pitifully underpaid workforce. Without that, we’re likely to see a continued pattern of reduced capacity in childcare facilities and facility closures.

First, some essential background: New York State does not have a unified childcare system. The State and its municipalities over time have layered different elements – each with their own policy supports – on top of each other, forming the childcare status quo.

It starts with unpaid care labor in the household, predominantly provided by women. On top of that we have full-day, year-round daycare in child care centers. There are also family-care providers – in essence, small businesses run out of the providers’ homes – that families can pay for out of pocket or, if eligible, with subsidies in the form of vouchers to spend where they choose. Most recently we’ve added universal Pre-K, provided in the non-profit and public sectors, including public schools.

As a result, there are early childhood educators working in a range of settings, each with its own requirements, some of which include different expectations for worker training.

Last year, the State made historic investments in childcare by expanding eligibility for subsidized care to more families and increasing the reimbursement rate to providers for that care.

Yet over the past year there has been a slow rollout of expanded eligibility due to agency backlogs, as well as delayed payments and rate increases to center- and family-based providers already cash-strapped from the pandemic.

That tie-up has exacerbated declines in facility capacity. It also exposes a foundational issue – early childhood educators’ compensation – that must be addressed in order to maintain, much less improve, the childcare system.

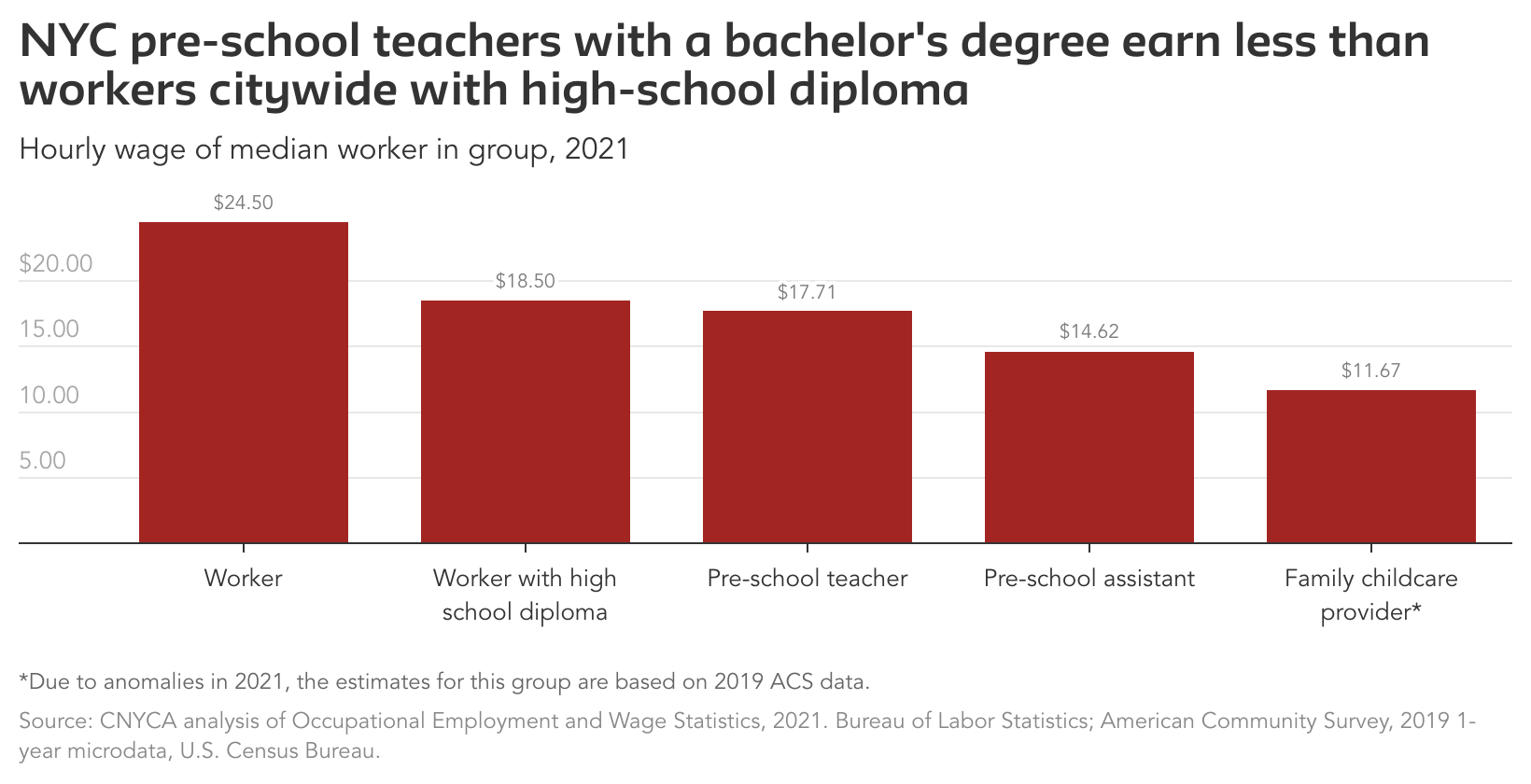

Those not working in public school Pre-K settings don’t earn wages on par with their neighbors and peers. In 2021 the median hourly wage in New York City was $24.50 per hour. However, the median hourly wage for New York City pre-school teachers was $17.71, and for assistant teachers (or childcare workers) it was $14.62, less than the City’s minimum wage. Family childcare providers, who run their own small businesses out of their homes, are paid even less. In 2019, the median family childcare provider made an estimated $11.67 per hour.

Some early childhood educators have reported leaving the industry for higher wages in fast food and other less-demanding industries. People working in childcare can find better paying jobs without having to do additional training. For example, the median family childcare provider or center-based childcare worker has a high school diploma. In 2021, the median wage of people with a high school diploma in New York City was $18.50 per hour. That’s twice what a family childcare provider is estimated to earn, $4 more per hour than center-based childcare workers make, and almost a dollar more per hour than for pre-school teachers, who typically have a bachelor’s degree or more.

Given the low wages in the industry, it is not a surprise that the childcare sector’s capacity is in crisis. Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, the state has lost over 7,000 seats for children under age five in registered childcare facilities. Family childcare providers were disproportionately impacted, with over 25 percent of them in New York City closing their businesses during this time.

In order to maintain – much less expand – capacity and improve quality, early childhood educators need to be paid more. For three reasons, the State is critical to making this possible.

First, it is hard for facilities to raise their rates to clients because of market pressures to keep childcare affordable.

Second, it’s also hard for them to increase revenue by serving more children, because State regulations require specific ratios of educators to children.

Third, those providing care through contracts with the City Department of Education or through vouchers paid by the State must navigate extensive bureaucratic processes to raise their contracted rates.

If the State Legislature raises the minimum wage this year (which would directly benefit many childcare workers), how will centers and family childcare providers meet that new requirement?

With that in mind, there are three things the State Legislature should prioritize this year.

First, the State should scrap its current “market-rate” methodology for setting the rates it pays providers; it seriously undervalues this work. Enacting legislation that would commit to a new provider reimbursement methodology by 2025, one based on the true cost of care, can put New York on a path to permanently pay childcare workers better.

Second, the State Legislature must also enact an emergency stop gap while these and other implementation issues are resolved. One simple and effective method, which the Washington, DC City Council provides a model for, is with a short-term workforce compensation fund to raise all childcare workers’ pay by at least $12,500 per year.

These payments delivered directly to workers, not through a grant application process, will help retain workers, who may be contemplating leaving for higher wages in other occupations, and effectively eliminate much of the disparities in income described above. It would translate to pre-school teachers making a median hourly wage of $23.50, and guarantee that childcare workers earn about $20 per hour – what the Upstate minimum wage would be by January 2026 if the proposed Raise the Wage Act is passed. It would also help to boost wages in and stabilize the entire center-based sector, where the majority of New York City’s Pre-K program is provided.

Third, to eliminate the bureaucratic hurdles that have kept providers from getting the rate increases legislated in 2022, the State Legislature should pass legislation to automatically pass on such increases.

Combining automatic increases with a $12,500 emergency compensation will have a particularly significant impact on the family-based sector of the system. That’s critical, because they currently serve two-thirds of the families who receive vouchers for subsidized care, and also because they are the most flexible part of the current system – with the ability to care for children of all ages and during non-traditional hours.

Together, these three initiatives can boost income for family childcare providers and wages for early childhood educators, which will stabilize the system as it exists now and create the possibility of growing it to meet the demands of the future.

Lauren Melodia is deputy director of economic and fiscal policies at the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School. This Urban Matters is based on her Jan. 26th testimony to the State Senate Standing Committee on Children and Families.

Photo by: InsideSchools